We knew we had made the right decision to hitchhike when we passed a field of sunflowers who had all turned their yellow and black faces away from the scalding sun and were drooping towards the dry, cracked ground. The mercury in my keychain thermometer was pushing its way past 40°C (104°F) but the turbulent wind crashing in through the truck’s open windows provided some relief from the heat. We were entering the Fergana Valley, one of the most fertile regions of Central Asia, which Kyrgyzstan shares with its neighbors, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

In 2010, the Fergana Valley was the scene of political and ethnic violence between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz people. As we drove through, it was hot and muggy but seemed relatively peaceful. Our convoy stopped at one point to eat a giant watermelon by a spring in the shade of a tree. We shared it with the other people who stopped there to rest and fill their water bottles. The driver of our truck pointed to cotton field in the hazy distance across the street and said, “Uzbekistan.” We were so close we could have touched it. But we wouldn’t enter Uzbekistan for another two months, not until after we had crossed the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan.

Kyrgyz boys and their bikes in a village outside Osh

Our truck broke down a few times on our way to Osh. Each time, we would hop out and the driver would jack up the cab until it looked like the truck was peering at something it found on the ground. The driver would then plunge his hands into the engine in a storm of wrenches, nuts and bolts, and grease. Moments later, the old diesel engine would roar back to life and we would take off again. But after the second breakdown, the truck had run out of patience and would quit whenever we stopped for more than a few seconds. Any time the engine’s rpm’s dropped below 1,000, it would sputter to a stop and our driver would dive back into the engine and bring it back to life.

When we finally reached Osh, the entire convoy stopped to help us unload our bikes and bags from the truck and to say goodbye. As I said goodbye to our driver, I pushed some money into his hand to help pay for gas or engine repairs. He looked a little perplexed by the gesture and I hoped it was because he wasn’t expecting to be paid for the ride and not because the sum was too small. After we said our goodbyes and watched our convoy merge back into the tumultuous traffic, we loaded up our bikes and set out in search of Bayana Guesthouse, a place recommended to us by some other cyclists in Bishkek. As we made our way toward the city center, we spotted our truck stalled out in the left-turn lane of a busy intersection amidst a fury of car horns. Unable to help, we wished them luck and continued on our way.

Erica standing beneath a giant statue of Lenin in Osh

Closer to the center of Osh, the streets were strangely deserted. Shops were closed and the streets were empty. We later realized that it was Eid al-Fitr, the last day of Ramadan, and that most people were home breaking their fast with a big feast. When we finally found Bayana Guesthouse on Lenin Avenue using the GPS on my phone, we checked into a small double room with a bathroom and fridge, parked our bikes in the courtyard, and stayed there for seven days.

I’m not sure why we stayed so long in Osh. There wasn’t really anything to do or to see there, except a rocky hill in the center of the city called Solomon’s Throne, which we never visited. But it was a nice enough place to rest and recuperate from life on the road. There was a restaurant with good, cheap cheeseburgers (Cafe Borsok, in the yurt-shaped building in the park next to Osh Market). But mostly I think we were procrastinating the start of the next and possibly most challenging chapter of our journey — crossing the Pamir Mountains.

When we finally shook off our inertia and bought supplies and tuned the bikes, we received some bad news about the state of the Pamirs. A record-breaking hot July and an unseasonably large amount of rainfall had melted away much of the snowpack in the Pamirs, leading to swollen rivers, landslides, and deadly mudflows. We checked online and learned that the M41, the Russian-built Pamir Highway, was blocked by a massive landslide just east of Khorog, a town sitting on the western edge of the Pamirs. I sent an email to the Pamir Eco-Tourism Association (PECTA) asking for more information and they confirmed that they M41 was indeed blocked. Our hearts sank. It seemed the only route through the impenetrable Pamir Mountains, and our only route forward, was closed off.

PECTA, however, suggested an alternate route through the Wakhan Valley. “Wakhan Valley? Isn’t that in Afghanistan?” I wondered. Google Maps showed that the north side of the Wakhan Valley is in Tajikistan while the south side lies in Afghanistan. The Panj River running down the middle forms much of the border between the two countries. Further googling turned up quite a few reports claiming that the Wakhan Valley is not only safe for traveling but is the most beautiful part of the Pamir Mountains. We were emboldened. We had a way through the Pamirs. We packed our bikes and headed south.

Some Kyrgyz kids in a village south of Osh

The M41 climbed gradually out of Osh, leading us through a dry, desert landscape interspersed with small villages built around green oases. As we entered one village, I was busy watching the road immediately ahead of me for potholes when I heard a loud thud. I looked up to see a small truck screech to a stop. Then screaming. Then crying. A small boy was lying motionless in the road. His brother or friend was wailing at his side. A small crowd gathered. A man ran to the truck and shouted at the driver. Moments later he ran back to the unconscious boy, scooped him up into his arms, carried him into the truck, and the truck drove off. Mothers led their inconsolable children back to their homes. Crying could be heard in stereo coming from all sides of the village.

Kyrgyz men wearing the kalpak, the traditional Kyrgyz hat

Drivers in Kyrgyzstan are dangerously stupid. They drive aggressively fast on narrow, bumpy, winding roads in old cars with bad brakes. And it doesn’t help that every shop in Kyrgyzstan offers a myriad of ludicrously cheap vodka for sale. The evidence of their dangerous driving is everywhere. There are so many roadside memorials and gravestones for people who have died in car crashes in Kyrgyzstan that you could mistake them for distance markers if it weren't for the names and dates of lifespans cut short etched into them.

We stopped for a moment in the shade of a shop (which sold more varieties of vodka than anything else) to recover from shock and work up the courage to get back on the road. When we finally did start pedaling again, we were too disheartened to go much further and soon began looking for a place to camp. We asked some guys pitching hay into a giant pile if they knew a place and they showed us to the apricot orchard beside their house. It was a beautiful place to stop and rest after a disturbing day.

Kyrgyz farmers making hay

Our campsite in the apricot orchard

Pretty soon after we pitched our tent, the neighborhood kids came around to check us out. “Boi boi!” they called out from a safe distance, chubby little fingers waving rigidly in the air. Somehow these kids had learned that foreigners great people by saying “bye bye,” which they pronounced like boi boi. We waved back at them and said, “hello!” and they gradually came over to inspect our bikes and our tent. When they saw my camera, they all excitedly lined up to have their photo taken.

Ethnically diverse young Kyrgyz faces

It felt bittersweet to be surrounded by so many happy, curious kids. It made me wonder about the boy who had been hit by a truck and hope that these kids would make it through life without a similar tragedy.

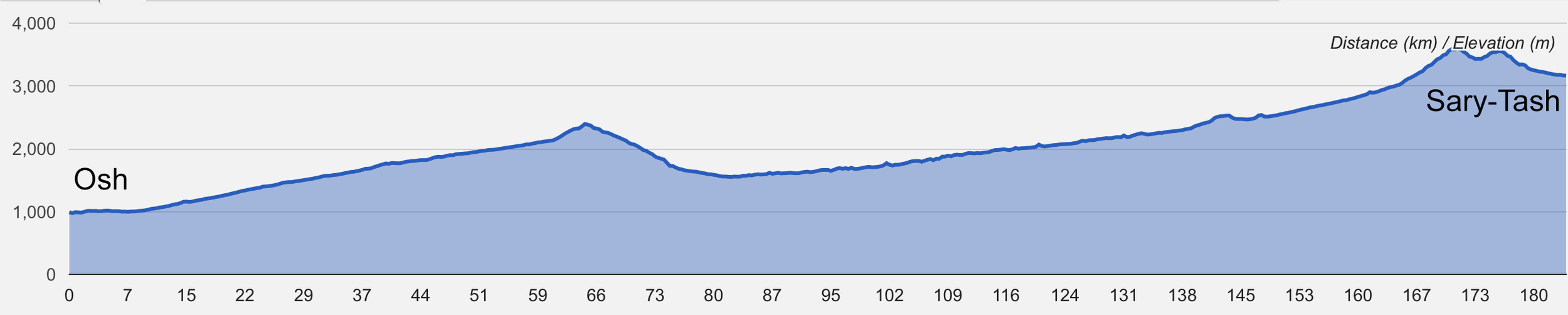

The next days passed mostly without incident and we made good progress towards the border. One night we pitched our tent in a bee keeper's garage to get out of the rain. The next day the weather cleared up and we had a nice secluded campsite by a river where we could wash our clothes and ourselves. The landscape grew more and more mountainous and on our third day from Osh we crested a 2,400 m (7,874 ft) pass before another long luxurious downhill cruise.

Bee hives with American flags stuffed in them

Erica charging up yet another steep climb

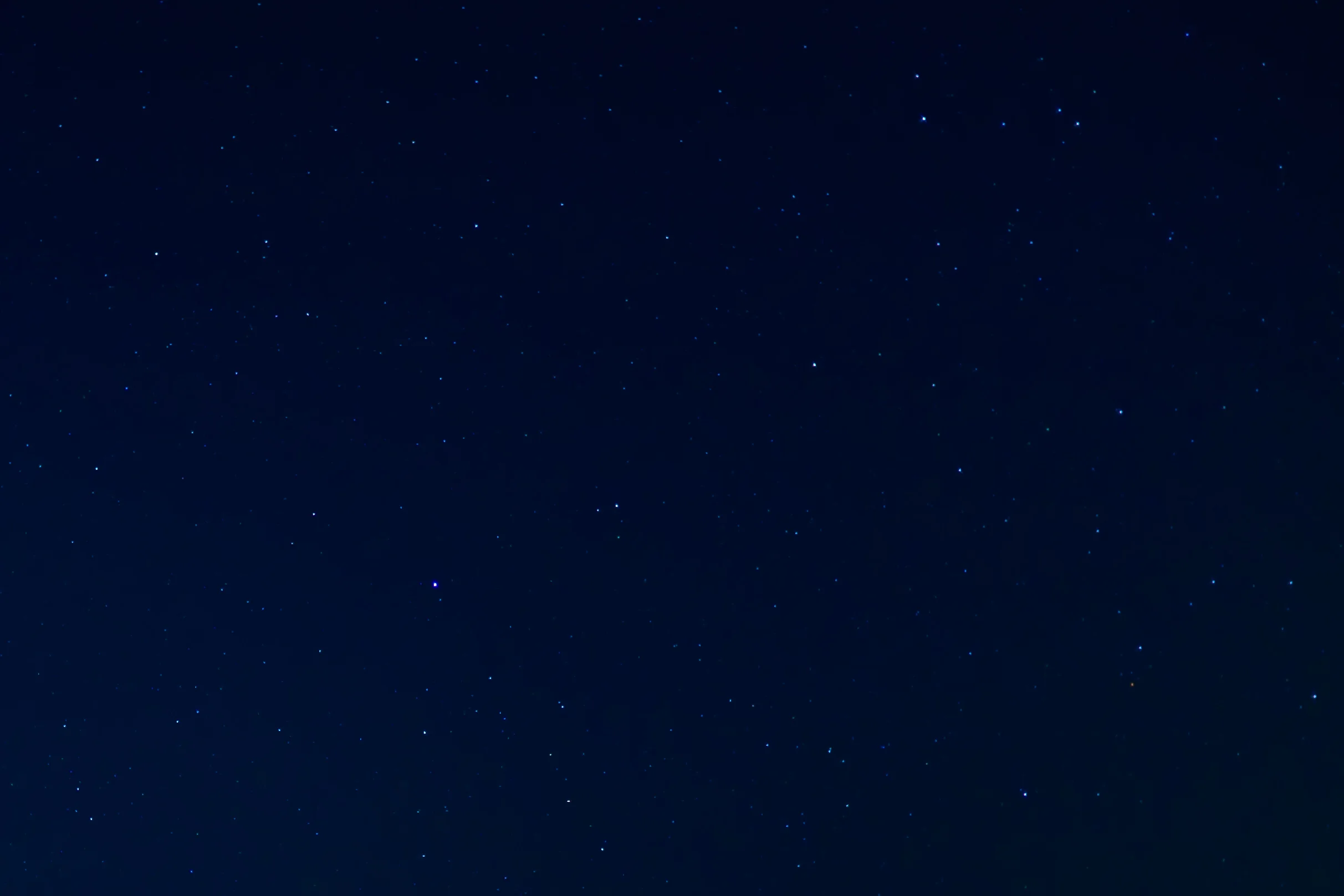

At the end of the fourth day we found a nice campsite at the end of a small trail quite far from the main road. After dinner we settled into our Big Agnes sleeping bag and fell asleep quickly. But sometime in the middle of the night I was woken up by the sound of a car stopping on the gravel. I laid there for a moment wondering if I had really heard it. But I knew it wasn’t a dream when I heard car doors opening and cheesy club music spilling out into the night. I sat upright, trying to wake up my half-asleep brain so it could devise a plan. My hands instinctively took up my headlamp and knife. I heard at least three voices approaching the tent. They sounded drunk. Just as I thought to wake up Erica, a light shined on the tent and her eyes shot open. I whispered to her that there were people outside the tent and put a finger to my lips.

Miles from anywhere but the drunks still found us

Erica's giant eagle feather

“Touriste, da?” came one voice. I did not answer. “Ruski ni pa niz meish?” (do you speak Russian?) the voice asked again.

“Niet,” I replied sternly, desperately trying to make my voice as deep an intimidating as possible.

“At-gooda?” (where are you from?) the voice demanded.

“Italia!” Erica snapped back, audibly furious for being harassed by these drunks. I grimaced, fearing how the revelation of a woman in the tent would affect our outcome. The voices muttered to each other for a brief moment which lasted hours.

“Bye bye,” said the voice and they got back into their car and drove off. We were lucky. That could have gone much worse. And until they drove off, I thought it was going to. I didn’t sleep much after that.

The next morning, Erica found a giant feather from a golden eagle and we attached it to her bike. It felt like a prize for passing the previous night’s challenge. We had 1,284 m (4,212 ft) to climb and 40 km (25 mi) to go over the Taldyk Pass before we reached Sary-Tash, the last town in Kyrgyzstan before the Tajikistan border and the Pamir Mountains.

We stopped for lunch just below a series of steep switchbacks which lead to the pass and watched trucks wind their way up them with unease as we slurped our instant noodles. The sky grew a darker shade of gray and a strong wind picked up that would alternately push us up and down the mountain depending on the direction of the winding road. We slowly but determinedly made our way up the switchbacks through the gusting wind and a light rain, getting passed occasionally by giant lumbering trucks. As we reached the top of the pass, the light rain grew into a steady downpour and we rushed to pull on our GoreTex jackets and pants. We topped-off our waterproof ensembles with florescent yellow reflective vests, courtesy of the Kunming Alleycat races, to stay visible in the gray and fading light. We then rolled down the other side of the pass into Sary-Tash.

More cute kids

The old man who rescued us from the cute kids

Serpentine switchbacks up the Taldyk Pass

Waterproof and high-viz

Sary-Tash felt like a truck stop at the end of the earth. It sits on the northern edge of the Alay Valley, a sprawling east-west trench separating Kyrgyzstan from Tajikistan. Ramshackle houses radiate out from a filling station at fork in the road which divides traffic into China and Tajikistan-bound lanes. Across the valley, the Pamir Mountains rise straight up like snowcapped sentinels guarding an impregnable fortress. When we arrived, dark clouds ominously shrouded the snowy peaks in the distance.

A young woman with jet black hair and snake green eyes checked us in to Tatina’s Guesthouse. There we met several other travelers: a hitchhiking German woman, two Dutch guys driving a Land Rover, and an Austrian mountaineering couple. The Austrians had just returned from an aborted ascent of one of the many 7,000 m (22,965 ft) peaks on the other side of the valley. A rockfall caused by the precipitously warm, wet weather had convinced them to abandon their summit bid. The weather forecast for the Pamirs predicted temperatures oscillating just above and below freezing and guaranteed rain for at least one week. We considered cycling the unpaved, uninhabited Pamir Highway in the freezing rain and imagined ourselves dangerously cold, wet, and miserable. After weighing our limited options, we made the difficult decision to hitchhike back to Osh to wait for better weather. We would have to put off our foray into the Pamir Mountains just a little longer.

Going our way?

Distance pedaled in this post: 185 km (115 mi)

Total distance pedaled to date: 863 km (536 mi)

Elevation profile provided by cycleroute.org